By Nicole Thom-Arens

During Christmas 2007, I was six months pregnant with my son Liam and I was deciding just what family traditions I wanted to pass on to my child. My husband and I had just returned from Scotland the previous spring. While there, I discovered the Thom family tartan to carry into my growing family, and that Christmas, I wanted to develop another level of my cultural identity — I wanted to learn how to make lefse.

When I decided to learn how to make the traditional Norwegian flatbread, there was no better person to teach me the art of lefse making than my grandma Mary Bisenius. During that time, in my hometown, the Bisenius lefse was, dare I say, legendary. My grandparents sold the treasured delicacy for years — they could never make too much and each sheet was precious. What made theirs stand out in a community full of Norwegians, though, was the homegrown potatoes. Many people make lefse with potato flakes, but never Jack and Mary Bisenius. When they lived in their house in the middle of town, Grandpa would grow the potatoes in the back garden, and, when the gardening became too much for my aging grandparents, they would get the potatoes from a local gardener.

All my life, the two of them have been retired. During my primary years, they owned a motorhome and experimented with spending winters in Florida, but Grandma preferred family and the cold to sunny skies a thousand miles away. They traveled together visiting Pearl Harbor, Portland, and Switzerland, to name a few. They were married for more than sixty years prior to my grandpa’s death. Grandma was a talker — there are many ways I am like my grandmother. She can fill a space with conversation better than most, which was good because Grandpa didn’t say much, but when he did, his words were well-thought and filled with passion. Summer days were spent on the golf course together, and they passed the long, cold winters indoors challenging each other through card games, but cooking is what the two of them did best.

They made lefse together for decades. Each November they began their task — making enough lefse for the holidays. They always did it together; Grandma rolled and Grandpa turned. Lefse making is, generally, a two-person job. The flatbread is rolled out just a tiny bit thicker than paper-thin and placed on a dry non-stick griddle to cook. The potato-based dough cooks in seconds and, without constant vigilance, the bread will burn. Once during my college years, I visited during one of the November cooking sessions and was asked to watch the griddle while Grandpa ran to the store. I think I only cooked one piece in the time he was gone, but those were the most stressful minutes with my grandmother that I have ever experienced. The bread is turned only once during the cooking process and it is done with a two-foot long, inch wide stick only slightly thicker than the lefse itself. I’m not a turner. Both duties take a certain level of patience, attention detail, and technique; I did not inherit the “turner” genes. The rolling, as I would find a few years later, is where I excel — turning took me longer to perfect.

Lefse is a bit of an addiction. When I lived in Missouri not knowing how to make lefse on my own, I craved it. If I was lucky, my cravings were satisfied with holiday visits up north, but there were a few years when I had to go without. In college at NDSU, I could buy lefse in the stores. It sufficed, but thick, tough, store-bought lefse held only mere similarities to what I grew up with. Good lefse, the best lefse, almost melts in your mouth. When enjoyed warm off the griddle with a bit of butter and a sprinkle of sugar, there isn’t anything better in the world I am sure, so I had to know how to make it on my own.

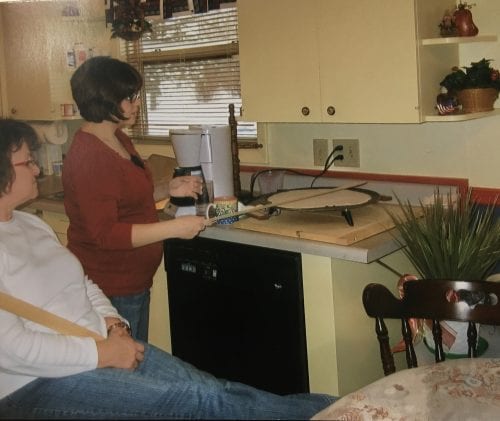

On the day of my first lesson, I was not sure Grandma really wanted to share her secrets. When I arrived at Grandma and Grandpa’s they were prepped and ready. Grandpa sat at the kitchen table with a cup of coffee. In front of him was a 9-by-13 cake pan full of riced potatoes — the essential ingredient to the best lefse. Grandma was across the kitchen at the counter ready to begin. I was set as the observer initially, but the time to put my skills to the test would come.

Lefse making is certainly a labor of love — a lesson I was eager to learn. This task, however, proved more difficult than I first expected partially because getting a recipe from Jack and Mary at that time was a near impossibility. The two of them had been cooking and baking together for so many years, whether at home or in the small café they ran together for most of my childhood until officially retiring a few years after I graduated college, that they did nearly everything by memory and had very few recipes actually written down. Luckily, lefse is one Grandma had preserved . . . sort of. The recipe she showed me that day was written according to the size of the “yellow bowl” Grandma always used for this task. As she stirred the second batch of dough, I transcribed the directions with a little help in translating the measurements, being I was not in possession of the aforementioned “yellow bowl.” I badgered my grandmother for approximate measures as she knowingly combined the riced potatoes, salt, sugar, melted butter, and whipping cream. Once the mixture was well incorporated, she more gently added the small amount of flour necessary to hold the dough together. Next, she separated the dough in two. Taking one of the halves, she formed the dough into a log-style shape before cutting off thirteen “handful” sized slices. These were left to rest for no more than ten minutes. Finally, it was my turn at the wheel, or I should say pin. One by one, I took each slice and flattened it on the lightly floured circular board used for rolling out the lefse. After kneading lightly, I began to roll — always starting from the middle and feeling the momentum of each pass of the rolling pin being careful not to apply too much pressure while attempting to keep the sheet an even circle. Once I had achieved the required thickness, or thinness, rather, I carefully slid my turning stick under the delicate sheet, rolling the lefse around the stick to transfer to the 400-degree griddle.

The process requires a surprising amount of concentration and focus. Much of what I accomplished was due to careful observation of my grandmother and tapping into my inner lefse sensei. Lefse making, as I learned that December day, is an art.

I had been rolling out the lefse for the latter part of the afternoon and my mom had been turning, while Grandpa and Grandma retired to supervising the roles they normally dominated, when Mom said she wanted to try rolling out a piece. It was a disaster.

“You have to feel the dough,” I said as she kneaded the dough asking how much kneading was too much. “There is no formula to it,” I said. “You just have to know when it is enough.”

I am not sure if she felt it, but she turned to the rolling. While my pieces were not all perfect circles, you could at least tell they were supposed to be circles. Mom’s piece more closely resembled Humpty Dumpty . . . after falling from the wall. It was closer to an oval and jagged around the edges, and the middle was riddled with holes she had attempted to pinch back together. We had a good laugh about her shortcomings as I took my turn at the grill with her patch-worked piece. I like to think my attempt at turning was more successful than Mom’s attempt at rolling, but I managed to ruin what little hope was left for this poor sheet by sticking the middle with the turning stick and leaving it a little too long on one side branding it with dark brown spots. The good news is Mom and I had the privilege of sharing that forlorn piece of lefse when it was still warm. It was just too pitiful to join the rest of the group that was keeping warm under the dishtowels on the kitchen table.

At the end of the day, Grandma stood back, looked at the beautiful towers of that treasured bread, and smiled.

“You did good,” she said with small nods of approval.

It was as close to a compliment as my grandmother gets and I savored her words.

Nicole Thom-Arens taught writing at Minot State University for seven years. She is currently the communications specialist for the NDSU Foundation and Alumni Association in Fargo. She and her husband, Tim, have an 11-year-old son, Liam. In their free time, they love traveling and attending major sporting events.